brucefan

EOG Dedicated

Some Truth, how refreshing

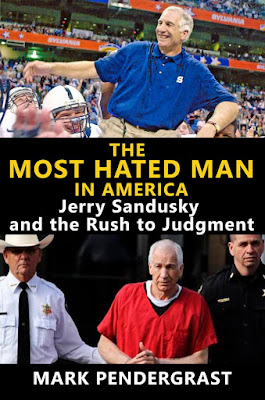

Federal Agent: No Sex Scandal At Penn State, Just A "Political Hit Job"

By Ralph Cipriano

for BigTrial.net

When he was investigating cold cases for NCIS, Special Agent John Snedden knew you always had to start from the beginning.

"Let's take a deep breath," he said. "And let's go back to square one, to the source of the original allegation, to determine whether it's credible."

On the Penn State campus in 2012, Snedden was working as a special agent for the Federal Investigative Services.

His assignment: against the backdrop of the so-called Penn State sex abuse scandal, Snedden had to determine whether former Penn State President Graham Spanier, who had just been fired, deserved to have his high-level national security clearance renewed. Snedden had to figure out whether Spanier had acted honorably at State College, and whether he could still be trusted to have access to America's most sensitive intelligence data.

The focus was on Spanier, but to do that investigation properly, Snedden had to unravel the mess at Penn State. He did it by starting at the beginning.

By going back eleven years, to 2001, when Mike McQueary made his famous trip to the Penn State locker room. Where McQueary supposedly heard and saw a naked Jerry Sandusky cavorting in the showers with a young boy.

But there was a problem. In the beginning, Snedden said, McQueary "told people he doesn't know what he saw exactly." McQueary said he heard "slapping sounds" in the shower, Snedden said.

"I've never had a rape case successfully prosecuted based only on sounds, and without credible victims and witnesses," Snedden said.

"I don't think you can say he's credible," Snedden said about McQueary. Why? Because he told "so many different stories," Snedden said. McQueary's stories about what he thought he saw or heard in the shower ranged from rough horseplay and/or wrestling all the way up to sex.

Which story, Snedden asked, do you want to believe?

"Everybody that he [McQueary] spoke to did not say it was sexual in any fashion," Snedden said. McQueary told Joe Paterno, Tim Curley and Gary Schultz "that it was not sexual, and that he didn't see it with his own eyes," Snedden said.

"What the hell exactly are you looking at," Snedden asked. "None of it makes any sense. It's not a credible story."

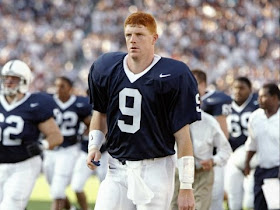

Back in 2001, Snedden said, Mike McQueary was a 26-year-old, 6-foot-5, 240-pound former college quarterback used to running away from 350-pound defensive linemen.

If McQueary actually saw Jerry Sandusky raping a young boy in the shower, Snedden said, "I think your moral compass would cause you to act and not just flee."

If McQueary really thought he was witnessing a sexual assault on a child, Snedden said, wouldn't he have gotten between the victim and a "wet, defenseless naked 57-year-old guy in the shower?"

Or, if McQueary decided he wasn't going to physically intervene, Snedden said, then why didn't he call the cops from the Lasch Building? The locker room where McQueary supposedly saw Sandusky with a boy in the showers.

When he was a baby NCIS agent, Snedden said, a veteran agent who was his mentor would always ask the same question.

"So John," the veteran agent would say, "Where is the crime?"

At Penn State, Snedden didn't find one.

Working on behalf of FIS, Snedden wrote a 110-page report, all in capital letters, where he catalogued the evidence that led him to conclude that McQueary, the only witness to the alleged crime, just wasn't credible.

Such as back on the Penn State campus in 2012, when Snedden interviewed Thomas G. Poole, Penn State's vice president for administration. Poole told Snedden he was in Graham Spanier's office when news of the Penn State scandal broke, and Gary Schultz came rushing in.

Schultz blurted out that "McQueary never told him this was sexual," Snedden wrote. Schultz was shocked by what McQueary told the grand jury. "He [McQueary] told the grand jury that he reported to [Schultz] that this was sexual," Schultz told Poole and Spanier.

"While speaking, Schultz shook his head back and forth as in disbelief," Spanier wrote about Poole's observations. Poole "believes it appeared there was a lot of disbelief in the room regarding this information."

To Snedden, McQueary's many different stories made him a non-credible witness.

"I've never had a rape victim or a witness to a rape tell multiple stories about how it happened," Snedden said. "If it's real it's always been the same thing."

But that's not what happened with McQueary. And Snedden thinks he knows why.

"In my view, the evolution of what we saw as a result of Mike McQueary's interview with the AG's office" was the changing of a story about horseplay to something sexual, Snedden said.

"I think it would be orchestrated by them," Snedden said of the AG's office, which has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

In Snedden's report, he interviewed Schuyler J. McLaughlin, Penn State's facility security officer at the applied research laboratory. McLaughlin, who's also a former NCIS agent himself, as well as a lawyer, told Snedden that McQueary initially was confused by what he saw.

"What McQueary saw, apparenty it looked sexual to him and he may have been worried about what would happen to him," Snedden wrote. "Because McQueary wanted to keep his job" at Penn State.

[McLaughlin] "believes Curley and Schultz likely asked tough questions and those tough questions likely caused McQueary to question what he actually saw. [McLaughlin] believes that after questioning, McQueary likely did not know what he actually saw." And McQueary "probably realized he could not prove what he saw."

There was also some confusion over the date of the alleged shower incident. At the grand jury, McQueary testified that it took place on March 1, 2002. But at the Sandusky trial, McQueary changed the date of the shower incident to Feb. 9, 2001.

There was also confusion over the identity of the boy in the showers, known officially in the Penn State scandal story line as Victim No. 2. In 2011, the Pennsylvania State Police interviewed a man suspected of being Victim No. 2. Allan Myers was then a 24-year-old married Marine who had been involved in Sandusky's Second Mile charity since he was a third-grader.

Myers, however, told the state police he "does not believe the allegations that have been raised" against Sandusky, and that another accuser "is only out to get some money." Myers said he used to work out with Sandusky since he was 12 or 13, and that "nothing inappropriate occurred while showering with Sandusky." Myers also told the police that Sandusky never did anything that "made him uncomfortable."

Myers even wrote a letter of support for Sandusky that was published in the Centre Daily Times, where he described Sandusky as his "best friend, tutor, workout mentor and more." Myers lived with Sandusky while he attended college. When Myers got married, he invited Jerry and Dottie Sandusky to the wedding.

Myers even wrote a letter of support for Sandusky that was published in the Centre Daily Times, where he described Sandusky as his "best friend, tutor, workout mentor and more." Myers lived with Sandusky while he attended college. When Myers got married, he invited Jerry and Dottie Sandusky to the wedding.

Then, Myers got a lawyer and flipped, claiming that Sandusky assaulted him ten times. Myers collected $3 million in what was supposed to be a confidential settlement with Penn State as Victim No. 2. But at the Sandusky trial, the state attorney general's office deemed Myers an unreliable witness and did not call him to testify against Sandusky. Instead, the prosecutor told the jury, the identity of Victim No. 2, the boy in the showers, "was known only to God."

Mike McQueary may not have known for sure what he witnessed in the Penn State showers. And the cops and the prosecutors may not know who Victim No. 2 really was. But John Snedden had it figured out pretty early what had gone down at Penn State.

Snedden recalled that four days into his 2012 investigation, he called his bosses to let them know that despite all the hoopla in the media, there was no sex scandal at Penn State.

"I just want to make sure you realize that this is a political hit job," Snedden recalled telling his bosses. "The whole thing is political."

Why then did the Penn State situation get blown so far out of proportion?

"When I get a case, I independently investigate it," Snedden said. "It seems like that was not the case here. It wasn't an independent inquiry. It was an orchestrated effort to make the circumstances fit the alleged crime."

How did they get it so wrong at Penn State?

"To put it in a nutshell, I would say there was an exceptional rush to judgment to satisfy people," Snedden said. "So they wouldn't have to answer any more questions."

"It's a giant rush to judgement," Snedden said. "There was no debate."

"Ninety-nine percent of it is hysteria," Snedden said. Ninety-nine percent of what happened at Penn State boiled down to people running around like chickens without heads yelling, "Oh my God, we've got to do something immediately," Snedden said.

"Ninety-nine percent of it is hysteria," Snedden said. Ninety-nine percent of what happened at Penn State boiled down to people running around like chickens without heads yelling, "Oh my God, we've got to do something immediately," Snedden said.

It didn't matter that most of the people Snedden talked to at Penn State couldn't believe that Graham Spanier would have ever participated in a coverup, especially involving the abuse of a child.

Carolyn A. Dolbin, an administrative assistant to the PSU president, told Snedden that Spanier told her "that his father has physically abused him when [Spanier] was a child, and as a result [Spanier] had a broken nose and needed implants."

Spanier himself told Snedden, "He had been abused as a child and he would not stand for that," meaning a coverup, Snedden wrote.

Snedden also couldn't believe the manner in which the Penn State Board of Trustees decided to dispatch both Spanier and Paterno.

There was no investigation, no determination of the facts. Instead, the officials running the show at Penn State wanted to move on as fast as possible from the scandal by blaming a few scapegoats.

At an executive session, the chairman of the PSU board, John Surma, the CEO of U.S. Steel in Pittsburgh, told his fellow PSU board members, "We need to get rid of Paterno and Spanier," Snedden said. And then Surma asked, "Does anybody disagree with that?"

"There wasn't even a vote," Snedden said. In Snedden's report, Dr. Rodney Erickson, the former PSU president, told Snedden that Spanier "is collateral damage in all of this."

Erickson didn't believe there was a coverup at Penn State.

"I was told it was just horsing around in the shower," Spanier told Erickson, as recounted in Snedden's report. "How do you call the police on that," Spanier had said.

On the night the board of trustees fired Paterno, they kept calling Paterno's house, but there was no answer. Finally, the board sent a courier over to Paterno's house, and asked him to call the cell phone of Steve Garban, chairman of the PSU board.

When Paterno called, Garban handed the phone to Surma.

Surma was ready to tell Paterno three things. But he only got to his first item.

"Surma was only able to tell Paterno that he was no longer football coach before Paterno hung up," Snedden wrote.

In Snedden's report, Spanier is quoted as telling Frances A. Riley, a member of the board of trustees, "I was so naive."

"He means that politically," Snedden said about Spanier. "He was so naive to understand that a governor would go to that level to jam him. How a guy could be so vindictive," Snedden said, referring to the former governor, who could not be reached for comment.

When the Penn State scandal hit, "It was a convenient disaster," Snedden said. Because it gave the governor a chance "to fulfill vendettas."

The governor was angry at Spanier for vocally opposing Corbett's plan to cut Penn State's budget by 52 percent. In Snedden's report, Spanier, who was put under oath and questioned for eight hours by Snedden, agreed that "there was vindictiveness from the governor:"

In Snedden's report, Spanier "explained that Gov. Corbett is an alumni of Lebanon Valley College [a private college], that Gov, Corbett is a strong supporter of the voucher system, wherein individuals can choose to utilize funding toward private deduction, as opposed to public education."

Corbett, Spanier told Snedden, "is not fond of Penn State, and is not fond of public higher education."

Spanier, Snedden wrote, "is now hearing that when the Penn State Board of Trustees was telling [Spanier] not to take action and that they [the Penn State Board of Trustees] were going to handle the situation, that the governor was actually exercising pressure on the [The Penn State Board of Trustees] to have [Spanier] leave."

The governor, Snedden said, "wants to be the most popular guy in Pennsylvania." Suddenly, the Penn State scandal comes along, and Corbett can lobby the Penn State Board of Trustees to get rid of both Spanier and Paterno.

The governor, Snedden said, "wants to be the most popular guy in Pennsylvania." Suddenly, the Penn State scandal comes along, and Corbett can lobby the Penn State Board of Trustees to get rid of both Spanier and Paterno.

"And suddenly Corbett" starts showing up at Penn State Board of Trustees meetings, where he was a board member, but didn't usually go. Only now Corbett "is the knight in shining armor," Snedden said. Because he's the guy cleaning up that horrible sex abuse scandal at Penn State.

"The wrong people are being looked at here," Snedden said. As far as Snedden was concerned, there was no reason to fire Spanier or Paterno.

""It's a political vendetta by somebody that has an epic degree of vindictiveness and will stop at nothing apparently," Snedden said about Corbett.

The whole thing is appalling," Snedden said. "It's absurd that somebody didn't professionally investigate this thing from the get-go."

As far as Snedden is concerned, the proof that the investigation was tampered with comes is shown in the flip-flop done by Cynthia Baldwin, Penn State's former counsel.

"You've got a clear indication that Cynthia Baldwin was doing whatever they wanted her to do," Snedden said about Baldwin's cooperation with the AG's office.

In her interview with Snedden, Baldwin called Spanier "a very smart man, a man of integrity." She told Snedden that she trusted Spanier, and trusted his judgment. This was true during "the protected privileged period" from 2010 on, Baldwin told Snedden. While Baldwin acting as Spanier's counsel, and, on the advice of her lawyer, wasn't supposed to discuss that period with Snedden.

Baldwn subsequently became a cooperating witness who testified against Spanier, Curley and Schultz.

Another aspect of the hysterical rush to judgment by Penn State: the university paid out $93 million to the alleged victims of Sandusky, without vetting anything. None of the alleged victims were deposed by lawyers; none were examined by forensic psychiatrists.

Penn State just wrote the checks, no questions asked. The university's free-spendign ways prompted a lawsuit from Penn State's insurance carrier, the Pennsylvania Manufacturers Association Insurance Company.

So Snedden wrote a report that called for renewing Spanier's high-level security clearance.

"The circumstances surrounding subject's departure from his position as PSU president do not cast doubt on subject's current reliability, trustworthiness or good judgment and do not cast doubt on his ability to properly safeguard national security information," Snedden wrote about Spanier.

Meanwhile, the university paid $8.3 million for a report from former FBI Director Louie Freeh, who reached the opposite conclusion, that there had been a top-down coverup at Penn State orchestrated by Spanier.

What does Snedden think of the Louie Freeh report?

"It's an embarrassment to law enforcement," Snedden said.

Louie Freeh, Snedden said, is a political appointee. "Maybe he did an investigation at one point in his life, but not on this one," Snedden said about Freeh.

What about the role the media played in creating an atmosphere of hysteria?

"Sadly, I think they've demonstrated that investigative journalism is dead," Snedden said.

If Jerry Sandusky was a pedophile, Snedden said, how did he survive a month-long investigation back in 1998 by the Penn State police, the State College police, the Centre County District Attorney's office, and the state Department of Child/Public Welfare?

All of those agencies investigated Sandusky, after a mother complained about Jerry taking a shower with her 11-year-old son. Were all those agencies were bamboozled? They couldn't catch a pedophile in action?

Another problem for people who believe that Jerry Sandusky was a pedophile: When the cops came to Sandusky's house armed with search warrants, they didn't find any porn.

Have you ever heard of a pedophilia case where large caches of pornography weren't found, I asked Snedden.

"No," he said. "Having worked child sex abuse cases before, they [pedophiles] go from the porn to actually acting it out. It's a crescendo."

"No," he said. "Having worked child sex abuse cases before, they [pedophiles] go from the porn to actually acting it out. It's a crescendo."

"I'm more inclined" to believe the results of the 1998 investigation by the D.A., the cops and the DPW, Snedden said. "Because they're not politically motivated."

Snedden said he's had "minimalistic contact" with Sandusky that basically involved watching him behave at a high school football game.

"I really do think he's a big kid," Snedden said of Sandusky.

Does he believe there's any credible evidence that Sandusky is a pedophile?

"Certainly none that's come to light," he said.

Does Sandusky deserve a new trial?

"Without a doubt," Snedden said. Because the first time around, when he was sentenced to 30 to 60 years in jail, Sandusky didn't have a real trial.

"To have a real trial, you should actually have real credible witnesses and credible victims," Snedden said. And no leaks from the grand jury."

It also would have been a fair trial, Snedden said, if the people who Sandusky would have called as defense witnesses hadn't already been indicted by the government.

While he was investigating Spanier, Snedden said, he ruffled some feathers at the state Attorney General's office. It came in the form of an unwanted phone call from Anthony Sassano, the lead investigator in the AG's office on the Sandusky case.

Sassano didn't go through the appropriate channels when he called, Snedden said, but he demanded to see Snedden's report.

Snedden said he told Sassano, sorry, but that's the property of the federal government. Sassano, Snedden said, "started spewing obscenities."

Snedden said he told Sassano, sorry, but that's the property of the federal government. Sassano, Snedden said, "started spewing obscenities."

"It was something to the effect of I will fucking see your ass and your fucking report at the grand jury," Snedden recalled Sassano telling him.

Sure enough, Snedden was served with a subpoena on October 22, 2012. But his agency sent the subpoena back saying they didn't have to honor it.

"The doctrine of sovereign immunity precludes a state court from compelling a federal employee, pursuant to its subpoena and contempt powers, from offering testimony contrary to his agency's instructions," the feds wrote back to the state Attorney General's office.

So what would it take to straighten out the mess at Penn State?

"The degree of political involvement in this case is so high," Snedden said.

"You need to take an assistant U.S. Attorney from Arizona or somewhere who doesn't know anything about Penn State," Snedden said. Surround him with a competent staff of investigators, and turn them loose for 30 days.

So they can "find out what the hell happened."

http://www.bigtrial.net/2017/04/fede...-penn.html?m=1

Federal Agent: No Sex Scandal At Penn State, Just A "Political Hit Job"

By Ralph Cipriano

for BigTrial.net

When he was investigating cold cases for NCIS, Special Agent John Snedden knew you always had to start from the beginning.

"Let's take a deep breath," he said. "And let's go back to square one, to the source of the original allegation, to determine whether it's credible."

On the Penn State campus in 2012, Snedden was working as a special agent for the Federal Investigative Services.

His assignment: against the backdrop of the so-called Penn State sex abuse scandal, Snedden had to determine whether former Penn State President Graham Spanier, who had just been fired, deserved to have his high-level national security clearance renewed. Snedden had to figure out whether Spanier had acted honorably at State College, and whether he could still be trusted to have access to America's most sensitive intelligence data.

The focus was on Spanier, but to do that investigation properly, Snedden had to unravel the mess at Penn State. He did it by starting at the beginning.

By going back eleven years, to 2001, when Mike McQueary made his famous trip to the Penn State locker room. Where McQueary supposedly heard and saw a naked Jerry Sandusky cavorting in the showers with a young boy.

But there was a problem. In the beginning, Snedden said, McQueary "told people he doesn't know what he saw exactly." McQueary said he heard "slapping sounds" in the shower, Snedden said.

"I've never had a rape case successfully prosecuted based only on sounds, and without credible victims and witnesses," Snedden said.

"I don't think you can say he's credible," Snedden said about McQueary. Why? Because he told "so many different stories," Snedden said. McQueary's stories about what he thought he saw or heard in the shower ranged from rough horseplay and/or wrestling all the way up to sex.

Which story, Snedden asked, do you want to believe?

"Everybody that he [McQueary] spoke to did not say it was sexual in any fashion," Snedden said. McQueary told Joe Paterno, Tim Curley and Gary Schultz "that it was not sexual, and that he didn't see it with his own eyes," Snedden said.

"What the hell exactly are you looking at," Snedden asked. "None of it makes any sense. It's not a credible story."

Back in 2001, Snedden said, Mike McQueary was a 26-year-old, 6-foot-5, 240-pound former college quarterback used to running away from 350-pound defensive linemen.

If McQueary actually saw Jerry Sandusky raping a young boy in the shower, Snedden said, "I think your moral compass would cause you to act and not just flee."

If McQueary really thought he was witnessing a sexual assault on a child, Snedden said, wouldn't he have gotten between the victim and a "wet, defenseless naked 57-year-old guy in the shower?"

Or, if McQueary decided he wasn't going to physically intervene, Snedden said, then why didn't he call the cops from the Lasch Building? The locker room where McQueary supposedly saw Sandusky with a boy in the showers.

When he was a baby NCIS agent, Snedden said, a veteran agent who was his mentor would always ask the same question.

"So John," the veteran agent would say, "Where is the crime?"

At Penn State, Snedden didn't find one.

Working on behalf of FIS, Snedden wrote a 110-page report, all in capital letters, where he catalogued the evidence that led him to conclude that McQueary, the only witness to the alleged crime, just wasn't credible.

Such as back on the Penn State campus in 2012, when Snedden interviewed Thomas G. Poole, Penn State's vice president for administration. Poole told Snedden he was in Graham Spanier's office when news of the Penn State scandal broke, and Gary Schultz came rushing in.

Schultz blurted out that "McQueary never told him this was sexual," Snedden wrote. Schultz was shocked by what McQueary told the grand jury. "He [McQueary] told the grand jury that he reported to [Schultz] that this was sexual," Schultz told Poole and Spanier.

"While speaking, Schultz shook his head back and forth as in disbelief," Spanier wrote about Poole's observations. Poole "believes it appeared there was a lot of disbelief in the room regarding this information."

To Snedden, McQueary's many different stories made him a non-credible witness.

"I've never had a rape victim or a witness to a rape tell multiple stories about how it happened," Snedden said. "If it's real it's always been the same thing."

But that's not what happened with McQueary. And Snedden thinks he knows why.

"In my view, the evolution of what we saw as a result of Mike McQueary's interview with the AG's office" was the changing of a story about horseplay to something sexual, Snedden said.

"I think it would be orchestrated by them," Snedden said of the AG's office, which has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

In Snedden's report, he interviewed Schuyler J. McLaughlin, Penn State's facility security officer at the applied research laboratory. McLaughlin, who's also a former NCIS agent himself, as well as a lawyer, told Snedden that McQueary initially was confused by what he saw.

"What McQueary saw, apparenty it looked sexual to him and he may have been worried about what would happen to him," Snedden wrote. "Because McQueary wanted to keep his job" at Penn State.

[McLaughlin] "believes Curley and Schultz likely asked tough questions and those tough questions likely caused McQueary to question what he actually saw. [McLaughlin] believes that after questioning, McQueary likely did not know what he actually saw." And McQueary "probably realized he could not prove what he saw."

There was also some confusion over the date of the alleged shower incident. At the grand jury, McQueary testified that it took place on March 1, 2002. But at the Sandusky trial, McQueary changed the date of the shower incident to Feb. 9, 2001.

There was also confusion over the identity of the boy in the showers, known officially in the Penn State scandal story line as Victim No. 2. In 2011, the Pennsylvania State Police interviewed a man suspected of being Victim No. 2. Allan Myers was then a 24-year-old married Marine who had been involved in Sandusky's Second Mile charity since he was a third-grader.

Myers, however, told the state police he "does not believe the allegations that have been raised" against Sandusky, and that another accuser "is only out to get some money." Myers said he used to work out with Sandusky since he was 12 or 13, and that "nothing inappropriate occurred while showering with Sandusky." Myers also told the police that Sandusky never did anything that "made him uncomfortable."

Myers even wrote a letter of support for Sandusky that was published in the Centre Daily Times, where he described Sandusky as his "best friend, tutor, workout mentor and more." Myers lived with Sandusky while he attended college. When Myers got married, he invited Jerry and Dottie Sandusky to the wedding.

Myers even wrote a letter of support for Sandusky that was published in the Centre Daily Times, where he described Sandusky as his "best friend, tutor, workout mentor and more." Myers lived with Sandusky while he attended college. When Myers got married, he invited Jerry and Dottie Sandusky to the wedding.Then, Myers got a lawyer and flipped, claiming that Sandusky assaulted him ten times. Myers collected $3 million in what was supposed to be a confidential settlement with Penn State as Victim No. 2. But at the Sandusky trial, the state attorney general's office deemed Myers an unreliable witness and did not call him to testify against Sandusky. Instead, the prosecutor told the jury, the identity of Victim No. 2, the boy in the showers, "was known only to God."

Mike McQueary may not have known for sure what he witnessed in the Penn State showers. And the cops and the prosecutors may not know who Victim No. 2 really was. But John Snedden had it figured out pretty early what had gone down at Penn State.

Snedden recalled that four days into his 2012 investigation, he called his bosses to let them know that despite all the hoopla in the media, there was no sex scandal at Penn State.

"I just want to make sure you realize that this is a political hit job," Snedden recalled telling his bosses. "The whole thing is political."

Why then did the Penn State situation get blown so far out of proportion?

"When I get a case, I independently investigate it," Snedden said. "It seems like that was not the case here. It wasn't an independent inquiry. It was an orchestrated effort to make the circumstances fit the alleged crime."

How did they get it so wrong at Penn State?

"To put it in a nutshell, I would say there was an exceptional rush to judgment to satisfy people," Snedden said. "So they wouldn't have to answer any more questions."

"It's a giant rush to judgement," Snedden said. "There was no debate."

"Ninety-nine percent of it is hysteria," Snedden said. Ninety-nine percent of what happened at Penn State boiled down to people running around like chickens without heads yelling, "Oh my God, we've got to do something immediately," Snedden said.

"Ninety-nine percent of it is hysteria," Snedden said. Ninety-nine percent of what happened at Penn State boiled down to people running around like chickens without heads yelling, "Oh my God, we've got to do something immediately," Snedden said.It didn't matter that most of the people Snedden talked to at Penn State couldn't believe that Graham Spanier would have ever participated in a coverup, especially involving the abuse of a child.

Carolyn A. Dolbin, an administrative assistant to the PSU president, told Snedden that Spanier told her "that his father has physically abused him when [Spanier] was a child, and as a result [Spanier] had a broken nose and needed implants."

Spanier himself told Snedden, "He had been abused as a child and he would not stand for that," meaning a coverup, Snedden wrote.

Snedden also couldn't believe the manner in which the Penn State Board of Trustees decided to dispatch both Spanier and Paterno.

There was no investigation, no determination of the facts. Instead, the officials running the show at Penn State wanted to move on as fast as possible from the scandal by blaming a few scapegoats.

At an executive session, the chairman of the PSU board, John Surma, the CEO of U.S. Steel in Pittsburgh, told his fellow PSU board members, "We need to get rid of Paterno and Spanier," Snedden said. And then Surma asked, "Does anybody disagree with that?"

"There wasn't even a vote," Snedden said. In Snedden's report, Dr. Rodney Erickson, the former PSU president, told Snedden that Spanier "is collateral damage in all of this."

Erickson didn't believe there was a coverup at Penn State.

"I was told it was just horsing around in the shower," Spanier told Erickson, as recounted in Snedden's report. "How do you call the police on that," Spanier had said.

On the night the board of trustees fired Paterno, they kept calling Paterno's house, but there was no answer. Finally, the board sent a courier over to Paterno's house, and asked him to call the cell phone of Steve Garban, chairman of the PSU board.

When Paterno called, Garban handed the phone to Surma.

Surma was ready to tell Paterno three things. But he only got to his first item.

"Surma was only able to tell Paterno that he was no longer football coach before Paterno hung up," Snedden wrote.

In Snedden's report, Spanier is quoted as telling Frances A. Riley, a member of the board of trustees, "I was so naive."

"He means that politically," Snedden said about Spanier. "He was so naive to understand that a governor would go to that level to jam him. How a guy could be so vindictive," Snedden said, referring to the former governor, who could not be reached for comment.

When the Penn State scandal hit, "It was a convenient disaster," Snedden said. Because it gave the governor a chance "to fulfill vendettas."

The governor was angry at Spanier for vocally opposing Corbett's plan to cut Penn State's budget by 52 percent. In Snedden's report, Spanier, who was put under oath and questioned for eight hours by Snedden, agreed that "there was vindictiveness from the governor:"

In Snedden's report, Spanier "explained that Gov. Corbett is an alumni of Lebanon Valley College [a private college], that Gov, Corbett is a strong supporter of the voucher system, wherein individuals can choose to utilize funding toward private deduction, as opposed to public education."

Corbett, Spanier told Snedden, "is not fond of Penn State, and is not fond of public higher education."

Spanier, Snedden wrote, "is now hearing that when the Penn State Board of Trustees was telling [Spanier] not to take action and that they [the Penn State Board of Trustees] were going to handle the situation, that the governor was actually exercising pressure on the [The Penn State Board of Trustees] to have [Spanier] leave."

The governor, Snedden said, "wants to be the most popular guy in Pennsylvania." Suddenly, the Penn State scandal comes along, and Corbett can lobby the Penn State Board of Trustees to get rid of both Spanier and Paterno.

The governor, Snedden said, "wants to be the most popular guy in Pennsylvania." Suddenly, the Penn State scandal comes along, and Corbett can lobby the Penn State Board of Trustees to get rid of both Spanier and Paterno."And suddenly Corbett" starts showing up at Penn State Board of Trustees meetings, where he was a board member, but didn't usually go. Only now Corbett "is the knight in shining armor," Snedden said. Because he's the guy cleaning up that horrible sex abuse scandal at Penn State.

"The wrong people are being looked at here," Snedden said. As far as Snedden was concerned, there was no reason to fire Spanier or Paterno.

""It's a political vendetta by somebody that has an epic degree of vindictiveness and will stop at nothing apparently," Snedden said about Corbett.

The whole thing is appalling," Snedden said. "It's absurd that somebody didn't professionally investigate this thing from the get-go."

As far as Snedden is concerned, the proof that the investigation was tampered with comes is shown in the flip-flop done by Cynthia Baldwin, Penn State's former counsel.

"You've got a clear indication that Cynthia Baldwin was doing whatever they wanted her to do," Snedden said about Baldwin's cooperation with the AG's office.

In her interview with Snedden, Baldwin called Spanier "a very smart man, a man of integrity." She told Snedden that she trusted Spanier, and trusted his judgment. This was true during "the protected privileged period" from 2010 on, Baldwin told Snedden. While Baldwin acting as Spanier's counsel, and, on the advice of her lawyer, wasn't supposed to discuss that period with Snedden.

Baldwn subsequently became a cooperating witness who testified against Spanier, Curley and Schultz.

Another aspect of the hysterical rush to judgment by Penn State: the university paid out $93 million to the alleged victims of Sandusky, without vetting anything. None of the alleged victims were deposed by lawyers; none were examined by forensic psychiatrists.

Penn State just wrote the checks, no questions asked. The university's free-spendign ways prompted a lawsuit from Penn State's insurance carrier, the Pennsylvania Manufacturers Association Insurance Company.

So Snedden wrote a report that called for renewing Spanier's high-level security clearance.

"The circumstances surrounding subject's departure from his position as PSU president do not cast doubt on subject's current reliability, trustworthiness or good judgment and do not cast doubt on his ability to properly safeguard national security information," Snedden wrote about Spanier.

Meanwhile, the university paid $8.3 million for a report from former FBI Director Louie Freeh, who reached the opposite conclusion, that there had been a top-down coverup at Penn State orchestrated by Spanier.

What does Snedden think of the Louie Freeh report?

"It's an embarrassment to law enforcement," Snedden said.

Louie Freeh, Snedden said, is a political appointee. "Maybe he did an investigation at one point in his life, but not on this one," Snedden said about Freeh.

What about the role the media played in creating an atmosphere of hysteria?

"Sadly, I think they've demonstrated that investigative journalism is dead," Snedden said.

If Jerry Sandusky was a pedophile, Snedden said, how did he survive a month-long investigation back in 1998 by the Penn State police, the State College police, the Centre County District Attorney's office, and the state Department of Child/Public Welfare?

All of those agencies investigated Sandusky, after a mother complained about Jerry taking a shower with her 11-year-old son. Were all those agencies were bamboozled? They couldn't catch a pedophile in action?

Another problem for people who believe that Jerry Sandusky was a pedophile: When the cops came to Sandusky's house armed with search warrants, they didn't find any porn.

Have you ever heard of a pedophilia case where large caches of pornography weren't found, I asked Snedden.

"No," he said. "Having worked child sex abuse cases before, they [pedophiles] go from the porn to actually acting it out. It's a crescendo."

"No," he said. "Having worked child sex abuse cases before, they [pedophiles] go from the porn to actually acting it out. It's a crescendo.""I'm more inclined" to believe the results of the 1998 investigation by the D.A., the cops and the DPW, Snedden said. "Because they're not politically motivated."

Snedden said he's had "minimalistic contact" with Sandusky that basically involved watching him behave at a high school football game.

"I really do think he's a big kid," Snedden said of Sandusky.

Does he believe there's any credible evidence that Sandusky is a pedophile?

"Certainly none that's come to light," he said.

Does Sandusky deserve a new trial?

"Without a doubt," Snedden said. Because the first time around, when he was sentenced to 30 to 60 years in jail, Sandusky didn't have a real trial.

"To have a real trial, you should actually have real credible witnesses and credible victims," Snedden said. And no leaks from the grand jury."

It also would have been a fair trial, Snedden said, if the people who Sandusky would have called as defense witnesses hadn't already been indicted by the government.

While he was investigating Spanier, Snedden said, he ruffled some feathers at the state Attorney General's office. It came in the form of an unwanted phone call from Anthony Sassano, the lead investigator in the AG's office on the Sandusky case.

Sassano didn't go through the appropriate channels when he called, Snedden said, but he demanded to see Snedden's report.

Snedden said he told Sassano, sorry, but that's the property of the federal government. Sassano, Snedden said, "started spewing obscenities."

Snedden said he told Sassano, sorry, but that's the property of the federal government. Sassano, Snedden said, "started spewing obscenities.""It was something to the effect of I will fucking see your ass and your fucking report at the grand jury," Snedden recalled Sassano telling him.

Sure enough, Snedden was served with a subpoena on October 22, 2012. But his agency sent the subpoena back saying they didn't have to honor it.

"The doctrine of sovereign immunity precludes a state court from compelling a federal employee, pursuant to its subpoena and contempt powers, from offering testimony contrary to his agency's instructions," the feds wrote back to the state Attorney General's office.

So what would it take to straighten out the mess at Penn State?

"The degree of political involvement in this case is so high," Snedden said.

"You need to take an assistant U.S. Attorney from Arizona or somewhere who doesn't know anything about Penn State," Snedden said. Surround him with a competent staff of investigators, and turn them loose for 30 days.

So they can "find out what the hell happened."

http://www.bigtrial.net/2017/04/fede...-penn.html?m=1